Is there still life in Still Life paintings?

Lot 1603 - Thomas Webster, XX, Oil on panel, A still life study of carnations, tulips, other flowers and fruits in a glass vase.

What do you think about Still Life paintings? Perhaps you haven’t really thought about them; I have to admit, I hadn’t really thought about them until recently. Our forthcoming Antiques, Collectables, Paintings & Prints auction has a varied assortment of paintings that has prompted me to think about how much of a transformative evolution the genre has experienced.

The subject matter of Still Life paintings has a rich history that spans cultures, periods, movements, and mediums, with origins that can be traced all the way back to Ancient Egypt where paintings of food adorned the interior of tombs. It was believed that these artistic representations would become a tangible feast in the afterlife. The most famous ancient Egyptian painting of food was discovered in the Tomb of Menna (Fig. 1). Similarly, Ancient Greeks and Romans also depicted inanimate objects. While they mostly reserved these subjects for decorative mosaics in the homes of the wealthy, they also employed the genre for frescoes, such as Still Life with Glass Bowl of Fruit and Vases, a 1st century wall painting found in Pompeii (Fig 2). There is an account that a famous Ancient Greek artist, named Zeuxis, painted some grapes that were so life-like that birds tried to peck at them. Unfortunately, none of Zeuxis’ works have survived (perhaps they were all eaten by hungry birds?!).

Fig. 1 - Still Life Found in the Tomb of Menna (Source)

Fig. 2 - Still Life with Glass Bowl of Fruit and Vases found in the House of Julia Felix in Pompeii (Source)

During the Middle Ages art was predominantly practiced in terms of religious requirements. Whilst Still Life paintings were not created per se, inanimate objects such as flowers and animals were painted with increasing realism in the borders of illustrated manuscripts. Some fine examples of this can be seen in the 15th century Book of Hours of Engelbert of Nassau (Fig. 3), with charming illuminations attributed to the Flemish artist Master of Mary of Burgundy. Displaying a brilliant display of vases, ceramics, flowers, feathers and insects.

Fig. 3 - Book of Hours of Engelbert of Nassau (Source)

While the early depictions of Still Life subjects are enchanting and thought provoking, it is not until the 17th century that the genre really came into its own and flourished. It went from being the lowest ranking in the hierarchy of artistic genres - its themes not deemed important enough by humanists to be worth painting - to the iconic Dutch Golden Age still life studies, which arose under a Protestant ethos that considered every element of God’s creation worth depicting. These paintings celebrate nature’s beauty, often bringing together flowers from different seasons, sometimes even from all four corners of the world and occasionally utilising tiny insects eating the leaves to serve as a reminder of the transience of life and the tangibility of beauty. Arguably the most prolific female artists of the period was Rachel Ruysch, whose botanical subject matters were meticulously executed, an exactitude perhaps inspired by her scientist father (Fig. 4). While each flower may have been studied individually from nature, the composition is the artist’s invention, created for decoration as well as for contemplation.

Fig. 4 - Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), Still Life with Rose Branch, Beetle and Bee, 1741 (Source)

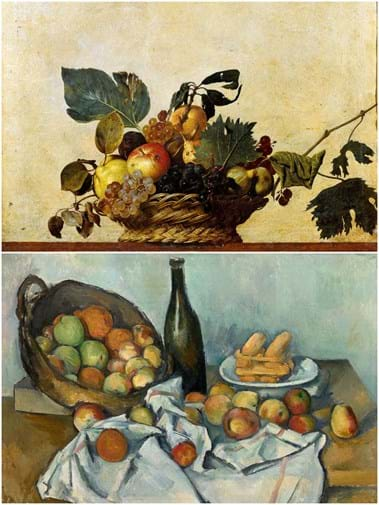

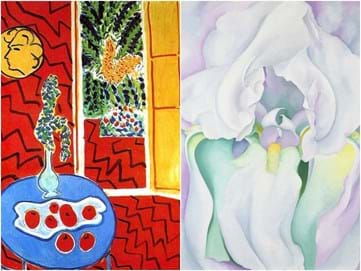

But can fruit, flowers, foliage, and man-made items such as wine glasses and jewellery really have a deeper meaning when they are so commonplace in the world? While the inanimate subject matter of Still Life paintings may not appear to mean very much at all at first glance, great intrigues can lay beyond even the most seemingly prosaic of surfaces. The French modernist painter Edouard Manet evoked the quiet potency of the genre with his statement “A painter can say all he wants to with fruits or flowers, or even clouds”. Which just about hits the nail on the head, perhaps the appeal for still lifes, both for artist and viewer, lies with the variety in style. Whether it’s Caravaggio’s enticing fruit baskets (Fig. 5), Cezanne’s toppling apples (Fig. 6), Matisse’s bright compositions (Fig 7), Georgia O’Keefe’s vivid, possibly sexualised, close-cropped blooms (Fig 8), or something in between - there really is simply something for everyone.

Fig. 5 - Caravaggio (1571-1610), Canestra di Frutti, c. 1599 (Source)

Fig. 6 - Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), Basket of Apples, 1895 (Source)

Fig. 7 - Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Red Interior, Still Life on a Blue Table, 1947 (Source)

Fig. 8 - Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986), White Iris, 1930 (Source)

Having the freedom to arrange the subjects creating their own composition, allowed the artist to express themselves, producing a portal into a kind of personal history, giving the spectator an insight into the artist’s mind. The artist’s aptitude to render the textures, details and play of light in a composition has the ability to vividly bring the items to life. As a genre, still life has provided artists with the opportunity to explore their relationship with the world and the different objects around them. What is notable is that the inanimate objects featured in still life artworks have changed over time, as the world has evolved.

The painting in our forthcoming auction that prompted me to think about Still Life as a genre, is by the English artist John Ernest Foster (Fig. 9). Instead of creating a traditional still life with natural produce, he chose to arrange items of shipping interest, incorporating a ship diorama, a Sunderland lustre jug, coins, shells, a ceramic parrott, etc. I feel that this captivating painting invites the viewer to ask questions - is it a sea captain’s desk, a collection of souvenirs, or something completely different?

Fig. 9 - Lot 1567, John Ernest Foster (1877–1968), Oil on canvas, A still life study with items of shipping interest to include dioramas, shells, coins, a Sunderland lustre jug, a ceramic parrot etc. Signed lower right. (View Lot)

Auction date: Thursday 18th & Friday 19th February - View our auction catalogue here

By Jen Mason